Reproduced from a 19 April 2010 article by courtesy of "Transport Trackers"

Given the recent stories on steel and price hikes we took a quick look sample historical reactions to price hikes. In April 1962, John F. Kennedy panicked after US steel companies proposed to raise steel prices $6/ton, as the proposed rises threatened his economic program. He went on TV, after earlier planning a multi-pronged campaign against Big Steel, to denounce the steel companies price change decision (“in ruthless disregard…” Please refer to http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x‐sIYl5C4mY). ...

If one thinks about it, a ton of steel was $20 ‐ $40 in the 1920s while an ounce of gold was fixed at $20.67/oz before the Fed appeared to get a present from Roosevelt in 1933 through the re‐fixing of gold at $35/oz. Steel per ton could loosely be put at $600 ‐ 800/ton today against about $1,100/oz for gold. Just an observation: Steel is up by a factor of about 20x in a century; gold is up by a factor of about 40x... We are not experts in steel and commodities, simply interested bystanders wanting to know more about many of the products going on ships, and their drivers.

Margins for the US steel industry were estimated, in an article of the day citing AP Business News, 10 April 1963, at about 4% net profit margin in 1962, down 15% from 1963. In comparison, US steel in 2009 had a negative EBIT margin over 15%, though this had come after a five‐year streak of EBIT margins averaging just under 10% prior to 2009.

Kennedy’s 1962 frontal assault on Big Steel led US steel companies to drop prices even below levels they had tried to raise them from (the attack coming when margins were 4%). By 1963, a number of papers came out on economic effects in the steel industry, with none other than Townsend’s Greenspan (remember Greenspan’s consultancy firm?) preparing a paper for the Society National Bank of Cleveland, among other papers, showing that US GDP between 1955‐62 increased 20% in real terms but that the steel industry, one of the centerpieces of the US economy at the time, was slowing in real terms, given only a 5% expansion during the period.

The article citing Greenspan (an analyst at Wellington submitted to the Financial Analysts Journal for November 1963) went on to speak of the US loss of market share to foreign producers. … In other articles we saw talk of 2.5 – 3.5% wage increase complaints from steel bosses. But overall, we got the feeling from most discussions that a lot of people walked around assuming flat costs, especially raw materials sourcing. Another thing people/ organizations did, as seen in many articles of the time available for viewing today via Google, is repeat verbatim press blurbs, so quite often price rise announcements simply stated the quantum of rise with no reference to base price (ie, it’s difficult to get one’s bearing on price points). … From reading articles from the 1920s on steel, on comparatively more turbulent times for steel prices than the late 50’s and early 60s, the price of steel had about doubled between pre‐ and post‐ WWI from about $20/ton to about $40/ton.

We had noted in recent weeks, some research reacting to iron ore price increases without appropriately adjusting for cost increases 1 . We still think more work needs to be done on this front, but some, among others, have flagged the impact of higher spot iron ore and quarterly contracting for some of the mills that historically relied more on annual contracting. Margin squeezes and demand patterns after price rises appear important questions/topics...

1 We could not believe one note we read from a large broker in late March ‘10, which raised steel price estimates for 2010 by LSD percentage points and put the average forecast for steel/ton for 2010 far below current price, with barely a mention of margin squeeze or indication of forward iron ore pricing views given the numbers laid out…. But we have seen other notes more recently doing a better job of forecasting margin squeezes. Still we would like to have seen a theme piece on steel looking at elasticities of demand in China and globally based on higher ore, coal, steel, etc..No doubt, someone is doing it. … Our long term view is that China needs to bring down production and demand which feeds into the construction of empty or low vacancy buildings, and stop stimulating for the sake of stimulating…China has taken baby steps in this regard, though in some sense even these steps have at times appeared more than that of the US Fed…But that’s just our view.

We have sourced stories from market reports and every effort is made to reflect news items fairly and accurately. However we can make no warranties of any kind as to the contents of reports and we shall not be held liable for damages. Our views represent our current opinions with respect to available data and information. Transport Trackers ©is a subscription‐based service for paid clients, therefore re‐transmission of our reports is not permitted. For more information please contact us atsales@transport‐trackers.com or charles@transport‐trackers.com.

So what’s changed in 50‐100 years of looking at price data and relationship?

Short answer: Not much, and everything. Today, repeating of press blurbs and sensationalism in headlines is perhaps still based on similar practices as in past. There are a lot more moving parts, to be sure. In the past, we could go years without a price change in an input. Later (in 60s, 70s??), some of that price stickiness was even down to command economy features, even in the US economy…Back then you’d get a US president dedicating speeches against price rises. Today we have infinite price changes of inputs and outputs, issues of over‐demand out of China, cheap capital from central banks, and…2The politics of steel perhaps haven’t changed as much as one would think, though. The politics were bad in the 1960s… and they are bad now.

What’s changed the most, in our view, is the order of things not just turning upside down (which Hegel or Marx would have understood/liked), but steel (and oil, etc) geopolitics are going in multiple directions at the same time.

In the heyday of the rise of the US as a superpower, it was about US dominance taking over from the British, etc. Everyone “knew their place...” 3The new good guys (US) were producing and dominating the market for key outputs. Sourcing contracts were in place and it was done more efficiently than the new bad guys (USSR) were doing it. Today, China (which was briefly aligned with the then bad guys) is producing more, if not most, efficiently, yet. And now it is sourcing at spot rather than on contract from developed and developing countries alike.

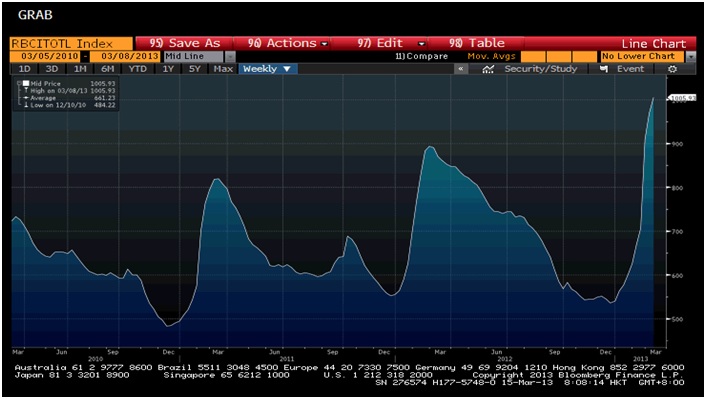

US Hot Rolled Midwest Avg $/ton, 1980 – Current (Monthly Series)

Source: Bloomberg

Notes

1 We could not believe one note we read from a large broker in late March ‘10, which raised steel price estimates for 2010 by LSD percentage points and put the average forecast for steel/ton for 2010 far below current price, with barely a mention of margin squeeze or indication of forward iron ore pricing views given the numbers laid out…. But we have seen other notes more recently doing a better job of forecasting margin squeezes. Still we would like to have seen a theme piece on steel looking at elasticities of demand in China and globally based on higher ore, coal, steel, etc..No doubt, someone is doing it. … Our long term view is that China needs to bring down production and demand which feeds into the construction of empty or low vacancy buildings, and stop stimulating for the sake of stimulating…China has taken baby steps in this regard, though in some sense even these steps have at times appeared more than that of the US Fed…But that’s just our view.

2Thisremindsus of a versionof “Stay” mostnicelyupdatedby JacksonBrownebackin the‘70s… (today… “wegottruckerson CB…”) from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jtuvXrTz8DY (1978 performance linked here)

3 …Until we got thinks like the Leontief Paradox… This takes us back to the Leontief Paradox on Heckscher Olin theorem problems, which was based on Leontief in 1954 (quite early on …) finding that the US, the most capital‐abundant country in the world, exported labor‐intensive commodities and imported capital‐intensive commodities in contradiction to the Heckscher‐Ohlin, which held that “a capital‐abundant country will export the capital‐intensive good, while the labor‐abundant country will export the labor‐intensive good.”

Author: Charles de Trenck / Publisher: SCMO