Published by Quartz on March 19, 2013 and reproduced by courtesy of Parag Khanna

Each week brings new revelations in the scale of the European horse meat scandal and yesterday came news of faulty, too-sheer yoga pants, but there is a common theme: the complexity of untangling the supply chains of producers, distributors and vendors spanning a dozen countries. From Romanian abattoirs to IKEA in the Czech Republic to frozen lasagna meals in Britain’s Tesco grocery stores, the process of tracing the origins of the horse meat, conducting food safety tests, and enforcing standards has overwhelmed regulators, laboratories, consumers, and food vendors. When HSBC’s airport jet-way campaign featured a panel that read, “In the future, the food chain and supply chain will merge,” this is surely not what it had in mind.

The horse meat scandal pertains to one sector, food, and one geography, Europe. But the supply chains of energy, finance, electronics, and much else have driven the matrices of business to envelop the world. Ever more, not less, multinationals depend on foreign markets for parts and profits. In many sectors, supply chains have become nearly impossible to untangle, even within just one or two countries. Whether BP, Transocean or Halliburton is responsible for the sinking of the Deep Water Horizon oilrig and massive subsequent Gulf oil spill in 2010 is still being arbitrated. Every day brings new headlines about supply chain confusion, exploited loopholes, and messes to clean up: in late February a Taiwanese company making Apple iPhone casings at a plant outside Shanghai was accused of polluting a local river.

Supply chains—the systems and networks of producers of goods and services that transform raw materials and components into products delivered to customers—are now an autonomous force in the world. Like globalization itself, they are greater than any one nation or economy. Some are entirely private, while others are hybrids of public and corporate actors. Many now connect Western and emerging market firms into a sprawling nexus that lacks a single headquarters and thus obeys no one jurisdiction. Supply chains have widened and deepened to such an extent that we must now ask ourselves: do we control the supply chains, or do the supply chains control us?

The new empire

With their cash reserves and legal protections, corporations act with greater agility than governments or households, who face greater constraints on their movements. In the 1980s, before “political economy” became a vogue graduate school major, the legendary London School of Economics professor Susan Strange coined the term “triangular diplomacy” to describe how multinational corporations (MNCs) have become so powerful that they engage on equal footing with governments, that are often mere “supplicants” to firms as they seek the capital, technology, and knowledge they cannot themselves generate. China’s rise is largely owed to its integration into global manufacturing supply chains, while India’s economy would not grow at all without liberalizing in ways that favor the expansion of private commercial supply chains.

Supply chains have effectively become their own form of governance, varying widely in nature depending on geography and sector, and with differing degrees of involvement by states, but undoubtedly transnational units of authority in their own right. The supply chain’s ambition is not territorial aggrandizement, but access to markets. They seek to oversee the greatest share of the flow of goods, capital and innovations. Expanding and improving supply chains is more important that boosting trade for the future of global growth. According to a new study by Bain Capital, if countries reduced border administration delays and improved telecom and transport infrastructure to just half the global standard, global GDP would rise by 5%. For supply chains, the extended market is the empire.

The paradox of the growing power of corporations is that even as their autonomy grows, their role as co-governors (or suppliers of governance) does as well. More than ever before, corporate supply chains shape and even create government regulation where they are lacking and provide public goods governments don’t. European hydropower companies write the legislation to govern their own industry in Nepal, since no such laws exist; private hospital chains in India enter poor backwaters and provide basic medical services where the government never has, as do private or philanthropic schools spreading literacy. As states come to depend more on corporations, the distinction between public and private, customer and citizen, melts away. Nowhere is this more true than a country like Nigeria, whose budget depends so existentially on Shell’s oil extraction, yet whose population expects public services to come from Shell as much as from its own government. In Nigeria, it is never clear who is in charge or who is exploiting whom.

Our dependence on many supply chains is nearly absolute. DHL can get any item anywhere in the world faster than anyone—even than the US military, one of its biggest clients, who uses it to transport everything from mobile battle stations to Halloween candy. When China suddenly banned the export of rare earth minerals in 2010, politically oblivious disk drive manufacturers woke up to their reliance on Chinese suppliers of these precious but essential components. The tsunami/earthquake that devastated Japan in early 2011 forced Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturers to scramble to new suppliers. With lagging Indian investment in the extractive sector, its diminished iron ore production has led to a spike of greater than $40 in the key ingredient for steel-making, swelling profits for BHP, Vale, and other mining giants. Commanding supply chains, not geography per se, is how winners and losers are determined today.

The tug-of-war between public and private power is far from settled. Indeed, it is just one symptom of far deeper shifts in global order that is still in the early phases of unfolding. With this complexity comes the need to re-assess, even supersede, some of the bedrock concepts of modern international relations, particularly the primacy of state sovereignty and territoriality. Instead, we need to appreciate how non-state actors are building global authority on the basis of wealth and resources, how loyalty can be horizontal to communities beyond vertical states, and how a wide range of players operate with increasing autonomy to pursue the own interests. Governance, both local and global, are open to all, and governments have to prove their utility to matter.

The global mobility of money

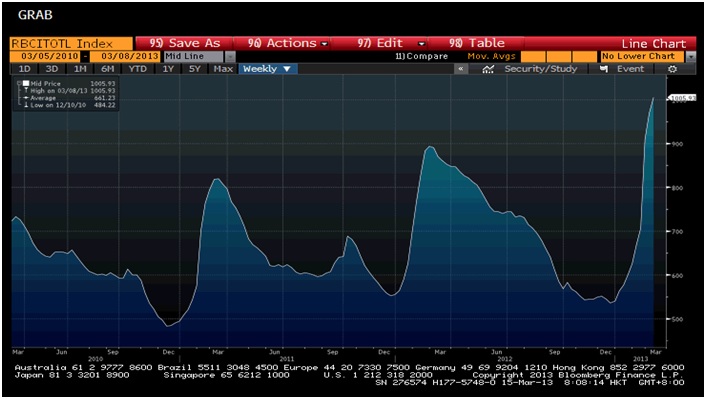

There is an adage that “who has the money makes the rules.” Sovereign wealth funds, currency traders, hedge funds, dark pools, institutional investors, asset managers, private equity firms, bond holders, and debt vultures are major independent players in driving, shaping, and pushing the world’s $225 trillion of global financial stock. The countless public and private players in the financial world compete for profits, ride each other’s waves, and discipline each other at the same time. Hedge fund managers spotted the weakness in the US housing market while Fannie, Freddie and mortgage lenders advanced the sub-prime mortgage policy. Hedge funds face less regulatory oversight than public companies, and are thus attractive to the wealthy. As the Economist recently reported, the re-privatization of public companies has restored financial control over to private hands. The total market value of privatized firms grew from less than $50 billion in 1983 to almost $2.5 trillion in 2009—roughly 10% of the world’s aggregate market capitalization, and 21% of the non-US total—and overall private capital assets are estimated at $21 trillion.

Globalization has dramatically enhanced the financial autonomy of even the world’s largest and seemingly most rooted multinational corporations. Whereas it was once an article of faith, as articulated in the 1950s by GM president Charles Wilson, that “What is good for the US is good for GM and vice-versa,” today it is far less clear. American multinationals increasingly enjoy the rule of law, investor protection, and innovative environment of the US, but derive over half their revenues from emerging markets. This applies across the spectrum from Hollywood films to automobile and pharmaceutical sales. As a result, MNCs can grow even during downturns at home while growth continues abroad. But globally distributed enterprises such as Apple, GE, IBM also hold massive assets offshore where tax rates are lower or nil – and sometimes relocate headquarters altogether as Halliburton did in moving to Dubai.

For nations, geography is fixed. For firms, it is an arbitrage opportunity. The Financial Times reported that Starbucks, Google, Amazon and other mega-companies pay less in tax to the UK than their share of revenue from it by using offshore holding companies from Belgium to Bermuda. An important component of a firm’s resiliency today is its capacity for regulatory arbitrage, the capacity to be geographically agile in mastering jurisdictions and regulations.

Of the 100 largest economic entities in the world, approximately half are companies, even excluding state-owned companies. Wal-mart has a market capitalization greater than all but the G-20 economies. Its annual revenues are greater than $446 billion (2012). In 2006, it alone was responsible for 12% of China’s exports. It is also the world’s largest private employer with a workforce of over 2 million people. Apple’s $600 billion market cap is larger than the GDP of over 120 countries. Its cash on hand is sufficient to bail out several ailing euro zone economies. In South Korea, Apple’s rival Samsung accounts for 8% of the national tax revenue.

Exxon Mobil, the largest energy company with a market cap of about $400 billion, represent how private energy companies like Shell and Chevron deliver stable global supply to the market while also providing local populations with employment and welfare—outlasting dozens of failed governments in the process. As Steve Coll points out in his recent book Private Empire, Exxon is the largest taxpayer in Chad, while Shell accounts for more than 21% of Nigeria’s total petroleum production of 629,000 barrels per day in 2009. In Iraq, Exxon’s direct dealings with the provincial government of Kurdistan could very well trigger an Arab-Kurd civil war that will force the country’s disintegration.

There is no doubt that the surge in state-owned enterprises in banking, energy, and other sectors represents a countervailing trend, especially given its prominence in crucial states such as China, Russia and Saudi Arabia. But it is also a trend that has reached its high-water mark for significant reasons. One is the suspicion of hostile state intent and subsequent blockage of cross-border state-owned enterprise (SOE) activity. Recent examples range from Dubai Ports World in 2006 to Huawei in 2011, and Australia’s blocking the merger with Singapore’s stock exchange. Another is the quality of corporate governance, whereby SOEs are often inefficient and slower to respond to changing market conditions. They also tend to lack the technological sophistication of private players. Because SOEs are bound to national governments, they cannot relocate when domestic circumstances worsen. Only private firms have agility when nationality becomes a liability.

We should be grateful for this trend. As Paul Midler documented in his supply chain tell-all Poorly Made in China, China’s SOEs face no market accountability; their only aim is to cut costs, often at the expense of standards. Witness the melamine contaminated pet food and baby milk scandals, and Mattel recall of baby bear toys whose eyes could fall out and choke children. The trust networks of factory managers and workers never extend past the next link in the supply chain, let alone to the broader Chinese or global consumer population. It was 6,000 Chinese babies poisoned by the melamine formula, not foreigners.

Western firms too want to cut costs; that is, after all, what drives outsourcing in the first place. But they face consumer pressure points that can have impact where government regulation falls short. Consumer activist and NGO expert groups have been crucial to certifying supply chains for diamonds and timber, and labeling dolphin catch-free tuna and GMO-free organic produce.

Auret van Heerden, head of the Fair Labor Association (FLA), gave a prominent TED talk in 2010 in which he used the phrase “Independent Republic of the Supply Chain.” He provided striking examples of how the outsourcing of outsourcing to suppliers for the production of mobile phones and pharmaceutical has led to large-scale human rights violations, drug contamination, and deaths from Congo to Bangladesh to China. But van Heerden is not an anti-corporate activist. The FLA has over 4,000 corporate members who work with NGOs, regulators, and other bodies to make supply chains safer and cleaner. It has pressured Apple, for example, to improve working conditions at FoxConn factories while Chinese authorities preferred efficiency at the lowest price.

Accountability means knowing where the buck stops—something that is increasingly complicated in a supply-chain driven world. Governments can’t fully control what they do not own. They need supply chains to carry out their own functions, and they need to partner with corporations and NGOs if they want to protect and serve their citizens. A franchise business can be more accountable due to strict rules set forth by a powerful parent company. McDonald’s has more capacity to inspect itself, and more incentive to do so to protect its brand, than any government can devote to monitoring efforts. All consumers worldwide are simultaneously citizens of the Independent Republic of the Supply Chain.

Diplomatic agency and responsibility

As multinational firms acquire wealth and market access through overseas expansion, their economic footprint and diplomatic reach becomes larger than many countries’ diplomatic services. The world’s largest democracy and a rising power such as India has fewer than 1,000 foreign service professionals, less than the number of lobbyists employed by a handful of multinationals in Washington and Brussels alone. Some African countries have foreign services that number only several hundred at the largest, many of whose primary task is to woo investment from such companies.

The Arab Spring has revealed a far deeper challenge than the corruption of Arab regimes. It is in fact just a symptom of the much broader entropy gripping much of the post-colonial world, from Africa through the Near East to South Asia. Dozens of states have squandered the last half-decade since independence. Cold War alliance politics takes some of the blame, but across these regions a succession of corrupt regimes have presided over populations that have tripled and sometimes quadrupled in size without building or refurbishing the requisite infrastructure, whether power lines, railways, housing, hospitals or schools. These conditions of general neglect have given rise to the reality of corporations serving as de facto “public” service providers.

Particularly in Latin America and Africa, supply chains serve as governance due to the absence of meaningful government. In Congo’s “copper belt” of Katanga, mining enclaves have become a new kind of post-colony that scarcely belongs to a country that barely exists. Mining companies in the Andean region educate and train their local managers who would otherwise be illiterate; oil companies in Guinea-Bissau fund AIDS treatment; and bottling companies provide housing for workers in Indonesia. There are no doubt many abuses of power, even crimes such as Chiquita’s usage of paramilitaries in Colombia to target union activists, but these take place within the context of supply chain service provision as compared to the outright neglect of the state. Even for what seem like the obvious sectors for resource rich countries to invest their scarce capital in, the private sector still does the public’s job. To this day, if you want to scope out a location for a mine in Zambia, you’ll need to lease a private plane from a company like K5 aviation to get to the site, still inaccessible by road. Public airports haven’t been built yet outside major population centers.

The privatization of major infrastructure, from American ports to British airports to the Panama Canal, applies de facto the world’s newest and most pervasive infrastructure: telecoms and the internet. Thirty corporations today control 90% of world internet traffic. Mega-grids that span entire regions connect once “off-grid” territories to world markets faster than any inter-governmental negotiation. Want to hire some techies to program African apps? Better hire them from Google-sponsored computer training centers in Nairobi, rather than public universities.

Even powerful nations face the paradox of being wealthy on paper, but unable to muster the fiscal investment to meet basic needs. Across Russia, the infirmed and elderly volunteer to be guinea pigs for Western pharmaceutical companies’ clinical trials given the precipitous decline in the country’s healthcare system. Even in America, rehabilitating once mighty Detroit has fallen on the shoulders of a troika of corporate moguls such as Dan Gilbert, founder of Quicken Loans, who along with the owner of the Detroit Redwings and CEO of Pensky Tires is funding myriad real estate redevelopment projects and a light-rail for the city’s downtown area.

Whether or not certain governments are in retreat, private-private diplomacy is becoming increasingly important to provide for global public goods. Private actors increasingly network with each other in ways that improve their overall effectiveness. For example, the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) now works directly with Wal-Mart along its supply chain to reduce carbon emissions. Neither is waiting for an inter-governmental climate treaty. Business for Social Responsibility (BSR), another NGO, has a staff of over 30 in China who are full-time consultants to Western and Chinese companies on improving labor conditions in factories. In the new supply chain diplomacy, form follows function: whoever can get the job done gets the deal.

Does it all add up?

The convergence of post-war Western economies created the conditions for the rise of the modern transnational corporation, and there is very little that can be done to reverse it. Protectionist policies that would undermine the international presence and standing of one’s own national champions by evoking painful reciprocal measures from other states. Inter-state diplomacy enabled our current phase of globalization and interdependence, but multinationals have become the key driver. Even the strong regulations imposed on Wall Street banks in the aftermath of the financial crisis have severe loopholes, and calls are growing stronger to revise aspects of the Dodd-Frank legislation that have harmed competitiveness.

There is no doubt that inter-state regulations and international law provide both the crucial opportunity as well as the ultimate constraint on the rising global power of private actors. Yet we must be careful not to assume sovereignty as a trump card when it clearly matters only where it is meaningfully enforced. There is also the claim that global firms require the stability and rule-in-law that is only provided by Western nations. But this fails to notice the rise of hundreds of globally competitive multinationals emerging from Brazil, the Arab world, and Asia that meet the criteria of product standards and corporate governance to be listed on stock exchanges worldwide. Furthermore, many global firms increasingly act as international partnerships, diminishing the centrality of any single headquarters, even in the US, in favor of local joint ventures and tailored strategies for each market.

Corporations and their supply chains are already critical players in global governance. The highest body in commercial arbitration, for example, is the privately run International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) based in Paris, which simultaneously helps craft collective business positions on international policy issues such as WTO trade negotiations. A nascent effort has begun to apply international humanitarian laws to business actors. The UN Voluntary Principles seek to regulate the activities of corporations operating in zones of conflict. While on the surface this appears to be an example of states strengthening their leverage over corporations, it should instead be viewed as a mutually beneficial process: firms are intimately involved in crafting the regulations, for which the UN is a repository, but its ultimate effectiveness ultimately hinges on the participating companies themselves.

The newly published Global Trends 2030 report of the National Intelligence Council titled “Alternative Worlds” includes a very plausible scenario titled “Non-State World” in which urbanization, technological advance, and capital accumulation accelerate the rise of private players that bend rules to maximize their productive power, particularly through the creation of special economic zones within and across national borders. As the scenario describes this trend, “It is as if the central government acknowledges its own inability to forge reforms and then subcontracts out responsibility to a second party. In these enclaves, the very laws, including taxation, are set by somebody from the outside. Many believe that outside parties have a better chance of getting the economies in these designated areas up and going, eventually setting an example for the rest of the country.”

America—and its companies—can only strengthen regulation where they participate in supply chains, such as th rough the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), which holds sway over American companies and those doing business with American companies. For better or worse, supply chains are the answer to supply chains. Supply chains, like globalization itself, are a complex system that is a whole greater than the sum of its parts. The food chain and the supply chain have indeed merged—as has much else.

Author: Parag Khanna and Ahmed El Hady / Publisher: SCMO