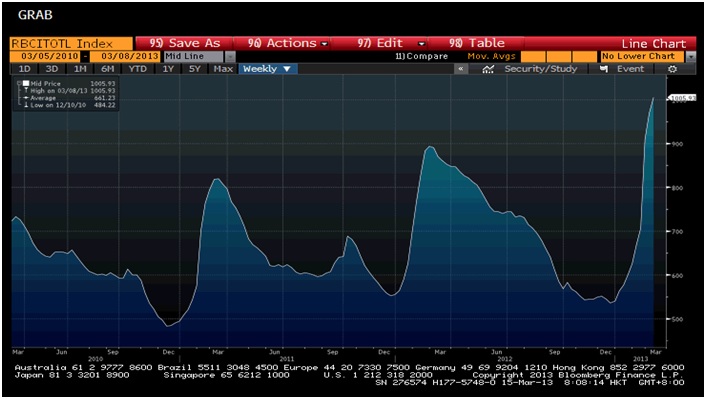

China Merchants has a knack for catching themes. China Merchants Holdings has been a decently managed company in the China context, holding decent port assets. But investors, mainland and foreign, always seem to get taken away by some idea of golden returns. In the late ‘00s there was all this fanfare about its Vietnam investment with billions of HK$ market cap added pretty much on the back of the concept.

Having Shanghai Port Group shares take off in the late ‘00s also helped propel the shares into the stratosphere for a while, as owning a stake in a Shanghai listed company offered investors participation in China rallies.

Yet, we know what happened to plans for Vietnam development. It was a total dud due to massive overbuilding of port assets. China Merchants let the project die quietly after a few permutations. Sri Lanka port expansion also was not without its controversies.

Ultimately Shanghai Port after 2008 turned out to be a little less exciting for 5 years or more – Until September 2014. Since then shares have doubled. This is one reason why shares of HK China Merchants Holdings perked up recently. But there is also the fanfare of China going big in global infrastructure as a result of a “new” Economic Silk Road initiative, which was laid out in NDRC in late March 2015 in a paper entitled Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road.

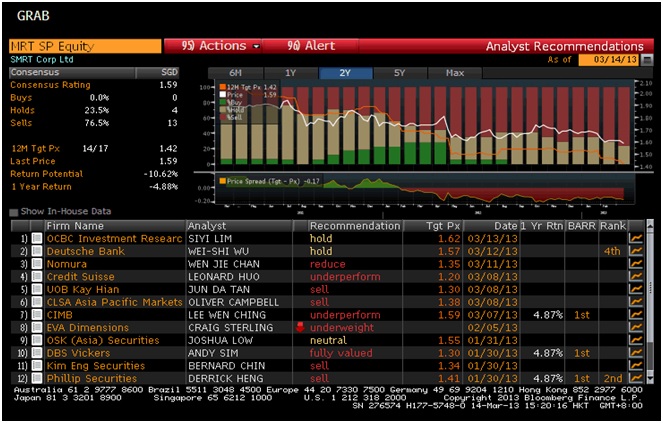

COSCO Pacific has not had it so easy since the late ‘00s. It hasn’t been able to recover from the perception of being a passive patsy for the poorly run COSCO parent and having a few more passive port investments as well as a boring container leasing business (which it sold parts thereof more than once). But, in its defense, it has always maintained 1) good disclosure, and 2) a good dividend distribution.

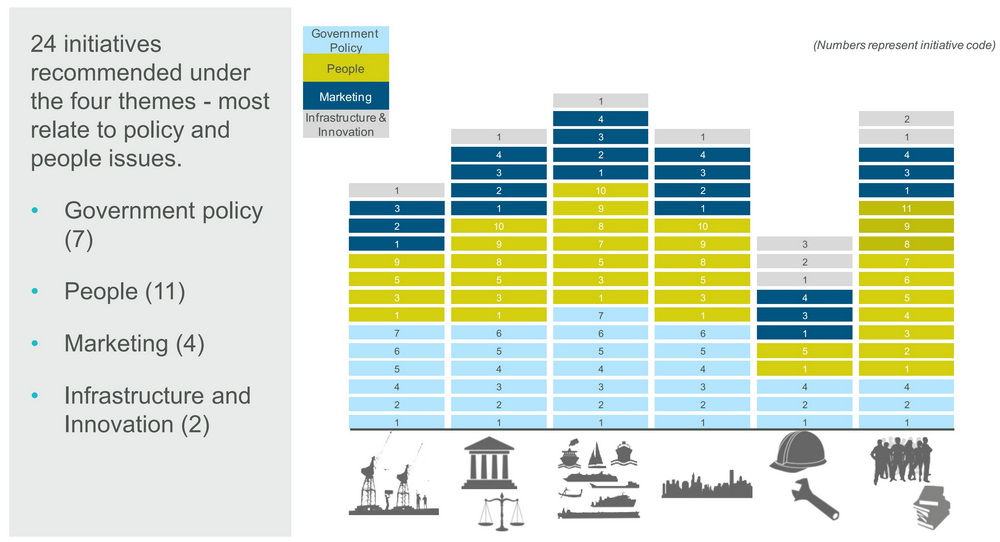

Port and infrastructure companies are certainly companies to look at as beneficiaries of the “new” economic silk road.

***

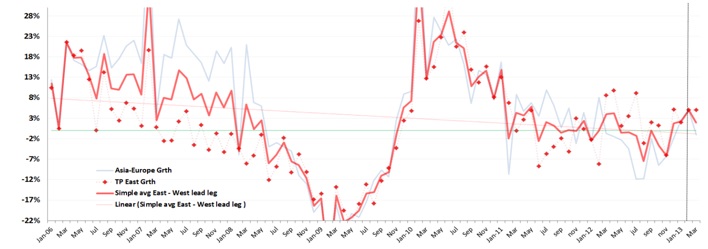

The Silk Road Economic Belt theme and policy statement out this time (see official China announcements and speeches) is different than the 20 year old “through train concept” for Asia to Europe via Central Asia (and not the money and share trading conduit between China and HK…). This was the old version for new trade growth avenues.

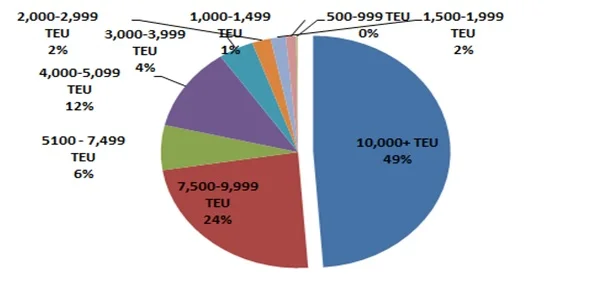

Over the last few years China has been backing a number of global infrastructure themes, from ports in Suez and Sri Lanka, to potentially theme parks in Cambodia, and ultimately to road and rail buildouts in SE Asia and new military bases and drilling rigs in disputed waters in the South Pacific.

China now is wrapping this in a comprehensive plan, seeking to show that the growth in the international strategic footprint is about increasing RMB transactions, and ultimately participating in a Chinese Economic Sphere that will even come with its on multilateral bank, which many countries are now warming up to.

It is a total package, marketed as global business expansion but also comprising a significant geo-political element with military sideshows. Move over Pax Americana. Here comes the Silk Rooster. It makes perfect sense. And it is not new. It is simply more front burner due to new focus from Xin Jinping.

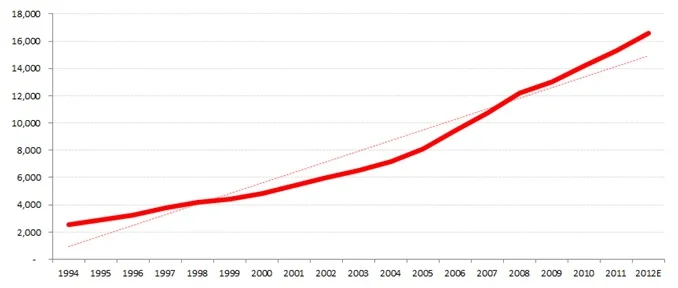

China Merchants didn’t just invest in a new global footprint ports last month. It’s been growing around the world for a decade or more, as have Shanghai Port and COSCO/ COSCO Pacific.

What’s more China didn’t just start building military bases in the middle of the South Pacific. It’s been laying down asphalt and train tracks in Laos for awhile. And if it can find financing that is supported by multilateral agencies, like its new Asia Infrastructure Bank, it will be building theme parks/property projects and roads, rail networks, ports, canals across the globe.

And a new surprise for some may be how substantial its influence in Thailand has become. The PLA and connected Communist Party members have been buying up and producing from jade, precious stones and metals mines in SE Asia for a long time. And one could not have done this without support from the authorities and the military. Recently CITIC (ultimately PLA linked) raised more funding for its re-capitalization from parties including Japanese trading houses and Thai Chinese. The Japanese are another key constituent of Thailand’s industrial base. From a Chinese perspective it is even more important to box in Japan’s influence around the Malacca Straits.

In some cases, China may have picked the wrong horse, such as Noble Group, which likely expanded too rapidly into commodity asset bases in places such as Brazil toward the top of the commodity cycle. And China has so far missed the boat on acquiring logistics companies rather than simply buying more container ships, bulk vessels and tankers. But it will figure it out.

Because China needs global expansion to replace stagnating China growth, China will pour a lot of resources overseas. And its large state owned companies will benefit immensely. For the moment these companies often don’t get the right cultural mix on international infrastructure projects, and they tend to go into projects in massive waves with too many Chinese workers, while leaving many behind along with support infrastructures. But this is 1) on purpose and 2) may get better regulated in future.

Imagine 50,000 workers descending on a small economy. The backlashes will eventually force some redirections. But at the same time China will have built a new mainland Chinese diaspora far larger than ex-Communist Party members who fled China with potentially as much as a trillion dollars.

Many countries, not just SE Asia, Japan or the US need to figure out how to integrate into China’s new global political economy. On the one hand investors can participate and benefit, while keeping tight leashes on credit policies. On the other hand, sovereign nations need to quantify and de-limit Chinese incursions into their national territory.

Author: Charles de Trenck / Publisher: SCMO